CLOAK/3.7iii

The alcoholic family, after every nightly tug-of-war the solid four-square stasis, the casket in the parlor,

unbudged, gaping, a survival of Stoicism, not survival itself, and every Sunday morning fresh

stigmata—Trishna's mother refused—I refuse, she said—to let this become an alcoholic family.

She got a referral from a doctor where she worked and with her health insurance booked some

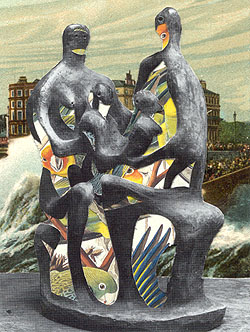

family therapy. Together they stared at articulate splotches, identifying cloaks of snow, cloaks of ash, aftermaths

of muffled grieving. At the first appointment, Trishna and her brother were both given

prescriptions for Phagacet. The family's therapist also recommended reading:

|

|

The numbers of people walking around for whom the bedroom is a terror corral, a place of

animal screaming, the anteroom to abattoir, but so it's daytime and they're shopping, doing the

laundry, crying at the movies—this great new book, When Abusers Put on Airs—go out and buy it,

go home and learn all about it.

|

Dutifully the family drove through winter storms to their weekly sessions. Soon Trishna's mother

conceived the idea of collaborating with a state welfare agency to provide off-season housing for

women and children in flight from dangerous homes—she would spend the developer's

settlement on renovations and heating for the bungalows. Trishna's father began another novel about

guilt, and drank less, and his view improved—the stormy winter, following the rainy fall, had raised the water table.

Rinsed and replenished, in the shy sun of the breezy lengthening days Lake Kenoma smiled and

frowned and smiled.

|